P is for Persimmons [2 recipes!], Plums, PDX Fermentation Festival and Picea breweriana (Brewer Spruce)

Will write for trees...

In August I met Michael Kauffman, author of several books about the ecology of the Klamath Mountain region, which is what you call the region if you live in California. If you live in Oregon, it is the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains. Or, as many now do, you could call it the Klamath Knot after a 1983 favorite (or cult) regional classic The Klamath Knot by David Rains Wallace. If you narrow in on the mountains I live amongst—Grayback, whose mass coaxes rain from clouds, Humpy and Little Humpy whose peaks brighten at first light, and the ridges in between that cradle us—you call it the Siskiyou Crest. A rugged mountain subrange of the Klamath Knot. It is an extremely ecologically diverse region.

Michael’s a conifer expert and advocate. I am a conifer lover so it comes as no surprise that I’ve read his book Conifer Country A natural History and hiking guide to 35 conifers of the Klamath Mountain region from cover to cover. Our region has the distinction of having more conifer diversity than anywhere on the planet. He was tabling at an event about the region and therefor was captive to all my questions.

I fancied myself a food producer for the first decade and a half as a steward on this land. Not so much for sale (though I did sell some fermented things) but to feed my family. In the last decade or so my thoughts and actions have fundamentally shifted—partly due to an empty nest, mostly due to understanding this land never wanted to be anything but a forest and that the forests here are changing. And so it is that I am planting a forest—one tree at a time.

This 40-acre patch of land was carved out of this region’s drier Mediterranean conifer forests. The patch is more of a hole really. When we moved here the forests hugged the edges of fields that had come from mowing the trees, burning the stumps, and adding sheep for half a century or more. An aerial view was that of the stark unnatural shape of a rectangle cut out of the forest.

While still more bare than forest, it is now an organic shape, with groups of trees banding together and linking across the expanse. Trees from the forest began to migrate into the open space as soon as the sheep were gone. We have also planted trees. Sometimes one or two at a time sometimes in mass plantings. We started with fruit and nut trees, of which many succumbed to lack of water, but around 100 still survive—feeding us and birds. As drought took hold, we started planting native forest trees—western red cedar, ponderosa pine, sugar pine and oaks. In 2016 we planted over 700 riparian trees along the creek at the edges of the pastures. In 2019, I planted 20 sugar pines that had been rescued from a compost pile. They were pot-bound, half survived.

The last two winters I planted giant sequoias because the one I won at a local bullfrog race eighteen years ago is now magnificent. In 2021 I planted 20 tiny seedlings, plugs, no more than 6-inches high, I babied them through the summer. Let’s just say that was a lot of buckets of water hauled. One by one they perished, mostly to rodents gnawing them down like a logger might fell a tree and leaving them for me to find. Four survived. This year I bought ten growing in one-gallon pots. They are tall enough to peek over the grasses and their finger-thick trunks are big enough to wrap with tinfoil. So far, no mortality.

The sequoias come as I am watching the pines and firs in the drought-stricken forests around me die at alarming rates. This has had me thinking about what native trees from the south would like some help migrating north. I asked Michael, “If there was one conifer from the southern parts of our region that would thrive where I am, what would it be?”

Without pause, he said, “Picea breweriana, or Brewer Spruce. It is one of the most beautiful and rarest of all our region’s trees. It has pendulous branches that give it its other common name, weeping spruce.

This tree has been around for around 65 million years, it would be a shame (putting it mildly) to lose this tree. Fossil records show its original range as far east as Nevada, northeast as Idaho, and north into central Oregon. It is now in small, isolated groves in the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains of northern California and southern Oregon. It survived ice ages and climate changes because of the microclimates these mountains offered.

These trees are rare and not found typically in nurseries, in fact in all the searching I’ve done far and wide I could only find 10 of them locally. This would be perfect to get another small grove started. Ideal planting time is right around the corner—November. The thing is they are $250 each, they are larger and in pots. Just one is a big lift for this writer’s income let alone two or more. The simple economics is 250 books need to be sold for each tree—we never sell that many in a month.

Driving home from the nursery a few weeks ago it hit me. I will write for trees.

Considering my tree habit, I am going to use 100 percent of my fall and winter Substack earnings to plant trees. You can join my planting virtually as a sponsor/paid subscriber. Founding member subscriptions will adopt one of these beauties and I will send you a picture of your adopted tree.

Speaking of trees

In August I wrote about my first, turns out, overzealous, planting of French prune plums. The season is nearly over. A big wind yesterday sent many to the ground. I have a few buckets of “pruneboshi” started because why not? We have made some fermented plum paste and a record amount of zwetschgendatschi, using my grandmother’s recipe. In this week’s paid post, I will share the recipes for both. In the meantime, the season is moving on to the next abundant fruit, whether we are ready or not.

In 2009 we planted ten American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) seedlings on our hillside. Because we started with seedlings, trees grown from seed, not a cultivar, they are all different. Eight survived and of those most are thriving. The first noticeable difference is leaf size. Some are large and luxuriantly elongated while others are short, looking like they are holding back. They have varying fruiting habits and types. For example, two trees have never born fruit and one of the tree’s fruits has much tougher skin, a longer tannic period, and the fruit turns purple. In the last few days, they are beginning to ripen beyond the cheek-drying astringency of the tannins.

I know this not just because I have been watching but because I saw our six-year-old grandson running down the hill from the trees using his hoodie to cradle a large bundle of persimmons.

I have to say my favorite is eating them as tiny snacks because it is such a rich seasonal flavor. My second favorite thing to do is make sorbet with them and add fermented ginger. My third favorite is persimmon vinegar. Our supply of persimmon vinegar (recipe below) is dangerously low and our crop of fruit is plentiful. This is the year I restock the larder.

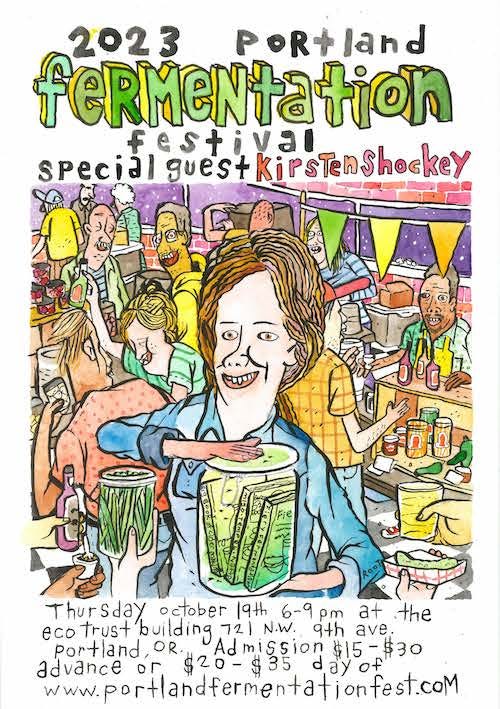

Portland Fermentation Festival aka Stinkfest

If you are in the neighborhood…

Join me (Tickets) and many other ferment nerds and fermenty enthusiasts at the PDX Fermentation Festival--back this year after a three-year hiatus.

Thursday, October 19th, 2023 from 6 to 9pm

at Ecotrust's Irving Street Studio and Rooftop Terrace the Pearl

721 NW 9th Ave. Portland, OR

Persimmon Ginger Sorbet

Makes about a pint and a half

Gingery and delightfully warming, this sorbet is rich with a velvety texture. Use any persimmon variety, but make sure they are fully ripe. We use our smaller American persimmons which takes a little more effort as they are small and often seedy. Hachiya, the large, bright orange ones must be completely soft — so soft you think it is too late because it looks like there is runny syrup inside the skin, which has started to blacken. The squat fuyu persimmons are less astringent and can be eaten as soon as the flesh feels soft.

The recipe for fermented ginger can be found here, or in our book Fiery Ferments (where this recipe first appeared.)

1 ½ pounds (680 grams) persimmon flesh (4 to 5 large persimmons)

1/2 cup (100 grams) sugar

2 teaspoons finely chopped Fermented Ginger

2 teaspoons ginger brine from pickles

Juice from 1/2 lemon

1. Carefully peel the persimmons. Combine the flesh with sugar in a blender or food processor. Process until very smooth.

2. Place in a bowl and stir in the ginger, brine, and lemon juice. Chill in the freezer for about an hour, or until mixture is very cold.

3. Churn in an ice-cream maker according to the manufacturer's instructions. When it is done, the texture will be like a soft-serve ice cream. Eat immediately or freeze in an airtight container (it will get slightly firmer).

Note: Don’t back off on the sugar, even though the persimmons are so sweet on their own. Some sugar is needed for good texture, though — it’s part of the science of freezing. The sugar keeps the water from freezing too much and creating crunchy ice crystals.

Wild American Persimmon Vinegar

Makes about 1 quart/ 1 liter

Korea has a long history with persimmon vinegar made from the small, native Meoski persimmons that are both sweet and tannic. According to the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity, this traditional vinegar was a staple made in most Korean households yet now is in danger of being lost. The Slow Food website describes the process of harvesting and drying the fruits and fermenting them in a raw alcohol, usually rice wine makgeolli. The wine takes on the persimmon fermentation and, when finished, the family’s vinegar mother is added.

My variation is local to my valley and uses native American persimmon in our homemade cider. Use any purchased cider or rice wine. I don’t dry the persimmons but ferment them in the cider and turn this into vinegar. It is lovely. Use cider or sake for this recipe.

1 pound (454 g) American persimmons

1 quart (1 L) hard cider, or 3 cups (710 mL) rice wine diluted with 1 cup (240 mL) water

1. Set the persimmons in a sanitized widemouthed half-gallon jar. Crush them lightly.

2. Pour the cider over the fruit. Stir well with a wooden spoon. Unlike with most ferments, you want to get some oxygen in the mix. However, make sure that the persimmons stay submerged. Otherwise they can become a host for undesirable opportunistic bacteria.

3. Cover the jar with a piece of unbleached cotton (butter muslin or tightly woven cheesecloth) or a basket style paper coffee filter. Secure with a string or rubber band, or screw on the ring from the jar over the cloth or filter. This is to keep out fruit flies.

4. Place on your counter or in another spot that is 75° to 86°F/25° to 30°C.

5. Stir again once a day for the first 5 or 6 days. After that, stir now and then, if you remember. You may see bubbles: that is good.

6. The ferment will slow down in about 2 weeks. Then it is time to strain out the persimmon mash. When you remove the cover, you may see a film developing on top. It is the beginning of the vinegar mother. Remove and set it aside. Line a strainer with a piece of butter muslin or fine-mesh cheesecloth and strain the mixture into a new sanitized jar. Press on the fruit and squeeze the cloth to get every drop out.

7. Put the almost-vinegar into a clean jar and cover again.

8. Check the vinegar in a month when you should have nice acidity. However, it may take another month or two to fully develop, especially if your environment is cooler.

9. Bottle the finished vinegar, saving the mother for another batch or sharing with a friend. Use immediately, or age to allow it to mellow and flavors to develop.

Thanks so much for these recipes! And also for your tree efforts. I once wrote about your state’s loss of our nation’s tallest Sitka spruce. You might like the piece. I’ll get a link for you.

Oooh I like the sound of this persimmon cider vinegar. Funny that, we just had our first taste of Philippine persimmons, they’re from up in the mountains up north where the cooler climate makes growing them possible, they were lovely! I saved seeds but doubt that they’d bare fruit where we are...

Lovely to hear about the tree planting and the rewilding of your piece of land. The summer sapling fatalities are familiar with me also but I’m getting better at it, we plant cassava around ours now and they quickly sprout and give some much needed shade.