L is for Lactic Acid, Lactate, Lacto-fermentaion, and Lactose

How these words can confuse and a recipe for lacto-fermenting leeks

Despite my best intentions and all the promises (and threats) I make to myself, when I am traveling I cannot keep up with any intentional movement—yoga, cardio work, PT exercises, or even a cat-cow stretch in the morning. I do find myself walking a lot and the nearly 6 weeks I spent in Europe was no exception. I love to explore. I logged an average of 20k steps most days traipsing through whatever presented itself from rocky or dusty paths to endless concrete. From unpopulated landscapes in the Scottish Highlands to moving as part of a sweaty a sea of humanity in festival transformed fields, between hedgerows, at Glastonbury Festival.

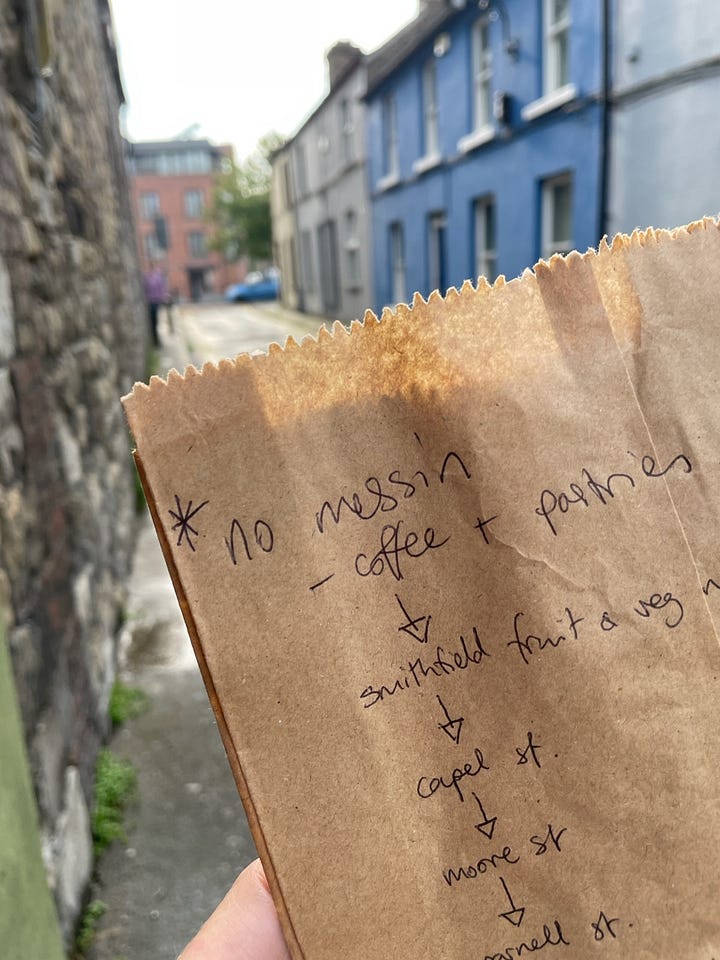

One walking highlight was in Dublin where we had a morning to explore the city. Our host, Aisling, owner of The Fumbally (DO go there if you are ever in Dublin!), scrawled out a list of spots to visit on the back of a paper bakery bag. Then she said, the fun will be to do this without the help of Google. Go analog. The challenge—find our way with no GPS from one landmark to another by asking for help from Dubliners instead.

My favorite part was remembering how beautiful chance interactions with humans are. It was a wee cheeky reminder of how travel was before we traded contact for interface. We had quick fun conversations that were spiced with local opinions—from why are you going that way the distillery is where you want to go its the other way, to Temple Bar is a tourist trap you’ll pay sorely for a beer to bemused wonder. We didn’t cheat until the very last stop for a cheese toastie at Loose Cannon Cheese and Wine. We’d walked in circles (turned out we were right there) and we were a bit hot, for it was a warm sunny day, and hungry for our elevensies snack. I am still dreaming about that cheese toastie.

All the walking does relieve me of some of my self-imposed exercise guilt. However, when I get home from a trip and began to get back into an exercise routine of sorts, I find that my muscles respond with a whole lot of drama as they remember what they used to do. There is the burn I might feel in the moment, when my muscles want to quit, and then there is the morning after (or, two mornings after) soreness. We’ve all been told this ouch is lactic acid built up in our muscles. This is something I’ve believed since my coach told me that when I was on my high school track team, but recent research is changing this narrative.

I decided last week when I was feeling spicy about my post-workout achiness to look up what was happening because I am afraid at some point my mind handed me an image of my muscles acting like they are pickled in sauerkraut—thank you brain, that wasn’t pretty. Clearly, I spend too much time fermenting vegetables.

I found myself falling down a rabbit hole! When I read that there is a collective confusion between lactic acid and lactate I decided we would explore lactic acid this week. It reminded me of a question I get at least once a month that is another similar matter of semantics.

“I am lactose intolerant. Can I eat lacto-fermented vegetables?”

Yes. Fermented vegetables contain no lactose or casein. The term lacto-fermented can be bewildering to people trying to navigate food intolerances. To begin with, the words are similar. But lactose is milk sugar. Lacto simply refers to the lactic acid produced by the action of bacteria in the Lactobacillaceae family—the lactic acid bacteria (LAB).

Additional confusion may arise because dairy ferments, such as yogurt and cheese, also rely on the Lactobacillaceae family of bacteria, to acidify milk. Many sauerkraut recipes further the confusion by calling for whey as a starter culture because it contains lactic acid. But whey is not necessary for lacto-fermentation. (I can’t wait for W when I can write about whey…)

Back to what is happening in our muscles. It is generally agreed upon that the delayed post-workout achiness comes from the micro tears from overworking muscles and your body responding with inflammation to heal them. It is not muscles pickled in lactic acid. In fact, it is not lactic acid, it is lactate that is to thank and to blame for that burn. Lactate is produced in our bodies to fuel our activities and prevent injuries. Colloquially, these two words have become interchangeable, and therein lies the confusion. From coaches to internet posts you will see most things refer to lactic acid. The difference is chemical. Lactate is lactic acid that is missing one proton and that is what our body produces, not lactic acid.

Today my exercise has been walking up and down the steep hill behind our home as I water trees that we planted years ago as part of a food forest. Every half hour or so I leave this relatively comfortable seat where I am consciously typing and unconsciously breathing and filling my lungs with oxygen. My lungs and bloodstream are supplying my cells with plenty of oxygen so that they have the energy to function. Cells use oxygen to produce usable energy (ATP Adenosine triphosphate an energy-carrying molecule) from the food we eat. As soon as my alarm tells me it is time to move the hose, I sigh deeply and think already…No, no, of course, that’s not it, instead, I pop up excited to trudge through the prickly dry grasses, weeds with small burrs, and what we call tarweed (Madia elegans). All these plants leave something with me--burrs and foxtails and sticky yellow strong-smelly resin. Oh, and it is hot. At some point when I am partway up the hill, cardio kicks in as does deeper breathing, it's steep and strenuous. At this point, my muscles require energy production that my lungs and bloodstream can supply. However, if I decide to keep marching up that steep slope into the forest beyond, which I do sometimes for the sheer pleasure of the view and brutal quick cardio work, at some point the energy production my muscle requires exceeds what my lungs can pump into the bloodstream. There are only a few seconds of stored energy in the muscles. These working muscles need to generate ATP (energy) quickly without oxygen, or anaerobically. Enter fermentation.

Many microbes, especially our bacterial friends in the genus Lactobacillus, use fermentation as their primary metabolic strategy. They aren’t the only ones. Cells in our bodies also rely on fermentation to generate usable energy. Fermentation isn’t just grapes into wine, and cucumbers into pickles, it is also responsible for keeping energy in our muscles when we keep exercising to the point of low oxygen. Fermentation is one of the pathways of glucose breakdown that can occur when oxygen isn’t around. In fermentation the only energy extraction pathway is glycolysis. Without getting into the chemistry, the cliff notes are that glycolysis is a series of reactions that extract energy from glucose of which lactate is a product. This fermentation does not generate energy it keeps glycolysis going during anaerobic respiration.

As our muscles intensely work they do become more acidic, which interferes with how well they function. Here is the part that was mind-blowing to what I have believed since those high school glory days, lactate isn't the cause of this acidity. Lactate is an antidote to a failing muscle. Lactate jumps in to help counteract the depolarization of the cells when muscles loose power. This is the burn we feel in the moment of intense exercise. So, if you are visiting and I have convinced you to march up the steep slope behind our home, and our muscles would likely start burning, we might stop and huff and puff a bit to get our energy back. As we get sufficient oxygen back into our system our muscles immediately stop yelling at us and our body switches gears and starts flushing the lactate.

Unlike popular belief, this lactate doesn’t hang around in the muscles, it heads to the liver where in a bit of biochemical recycling it can be used to produce more glucose for future energy. For those of you that synthesize information better with pictures here are some good graphics showing cellular respiration. You can see where fermentation fits into how our cells work.

Fermenting our food is a small way that within the comfort and security of our lives, we can connect a little more with the microbes that are all around and in us. We can make friends with the microbes that transform our food and in doing so become a little less afraid of them. How cool is it that we all get energy from glucose? Watching a jar of cabbage turn into sauerkraut has similarities to running up a hill and it's not lactic acid. Fermenting is a connecting point that grounds us in our own biology and the biology around us. For so long, the prevailing sense of many humans is seeing themselves as other, somehow detached from nature. We are nature and it is us despite all that we have constructed around ourselves to feel other. The similarities and understanding of the metabolic pathways of one thing can help us understand another. In this way, there is beauty in that jar of fermenting vegetables.

Leeks

The past few weeks I have been enjoying local leeks. When I saw them at the market, I knew it was time to make Leek-chi. We have been enjoying this simple leek ferment for many years now. Fermented leeks have sublime flavor and the microbial transformation mellows the sometimes bitter bite of the greens, so I always use the entire leek.

Leeks lend themselves to larder ferments—flavor building, nutritionally dense, convenience foods. These are ferments that you can either use as they are as a garnish or condiment or to use as a base of another dish. This Leek-chi is exactly that. I often will start a sauce or braised veggies by sauteing some of this in a little bit of fat. This saves time at the moment of cooking, since I make the ferment in advance.

Last week I started experimenting with leeks again. Again with idea of time saving ways to bring that allium aroma to a meal quickly. (This is a theme for me.)nRight now, we have a favorite weekend breakfast that uses leeks and preserved lemons. It occurred to me that while leeks are in the peak of freshness here in Oregon, I should see what other meal starters I could come up with. So far the leek and lemon is not disappointing. I will share more about this and other leek ferments in this week’s paid post. Meanwhile, keep scrolling for the Leek-chi recipe.

Leek-chi

yield: about 1 quart (946 ml)

This ferment, based on the kimchi triad of garlic, ginger, and chile, has a surprisingly mild quality. Its appearance is striking—it develops a remarkable yellow color that is pretty on the plate. Dollop this into a soup right before serving, or inside a grilled cheese sandwich for flavor and pizzazz!

Note: If you prefer a sourer ferment, add a teaspoon of sugar to the mixture before fermenting.

11/2 pounds (675 g) leeks, white and light green parts

2 teaspoons (11 g) unrefined salt

2 large cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon (6 g) ginger, finely grated

1 tablespoon (9 g) sesame seeds, lightly toasted

1 teaspoon (1.5 g) dulse flakes

2 teaspoons (5 g) dried chile flakes (or to taste)

Grape leaves or parchment paper, to top the jar or crock

1. Slice the leeks thinly and place in a large bowl. Sprinkle in the salt, toss to coat, then massage the leeks by hand or press with a tamper for about a minute to begin the brine development. Add the rest of the ingredients and mix in to distribute evenly.

2. Transfer the mixture to your fermentation vessel, a handful at a time, pressing down to remove air pockets as you go.

3. Place grape leaves or parchment paper on top. Follow the instructions for your fermentation vessel. For a jar, if using the burping method (page 000) make sure there is little airspace and seal the lid tightly. Burp daily or as needed. Alternatively, top the ferment with a quart-sized ziplock bag. Press the bag down onto the top of the ferment and then fill it with water and seal.

4. Set your fermentation vessel on a plate in a spot where you can keep an eye on it, out of direct sunlight, and let ferment for 8 to 16 days. The ferment is ready when the leeks change from a verdant green to a yellow-green, their pungency softens, and the flavor becomes slightly sour.

5. To store, transfer to smaller jars, if necessary, and tamp down to make sure the leeks are submerged in the brine. Tighten the lids and set in the refrigerator, where the ferment will keep for 1 year.

Thank you so much for this Kirstin. I get asked these questions often, but haven’t got around to actually research it. I really appreciate you doing so, and present it in layman’s speak!