E is for Eggplant

Taking fermentation beyond brine and using moisture reduction for tasty ferments.

This week our landscape has been hidden under piles of snow, more snow than we have seen in a few years. It is a charade though, what I really feel is a landscape teeming with energy. Spring is sweeping winter out the door; microbes, birds, buds, seeds, and sprouts are plumping up and ready to surge forward with green and growth. We are not out of drought by any stretch but the moisture is welcome and coursing through a parched landscape and allowing sap to flow in trees. It feels that the life that has made it through is vibrating with vitality.

In a funny way, my week has gone in exactly none of the ways I thought would. Instead, so many things have presented themselves to me in the form of thought-provoking reads, inspiring presentations at Kojicon, deep conversations, and a few long walks. This is the same surge of spring—but in me. I recognize this here-we-go in the same way that at the end of summer, I feel one breeze at the end of an August day that tells me we are settling. In practical terms, this means yours truly has had many false starts to this dispatch because I haven’t been able to settle on one topic. (I have an idea and goal, that ends in eggplant, though admit I am still not completely sure what path I might be taking you on.)

Years ago, when I first began to lactoferment vegetables, I have to admit, didn’t fully understand what was going on but I knew that everything needed to be submerged in a brine. In my mind, to keep things anaerobic, the juicier the better. In fact, it seemed to me the more brine on top of the vegetables, the more of a blanket, or layer of protection there was between my ferment and all the things that wanted to grow on top. As I understood more, I still found this to be a truth. Christopher and I even came up with a little saying to help our students – Submerging in brine, conquers evil every time. While this is true that a juicy brine from cabbage or poured over vegetables is what makes the whole thing work it is less about the liquid being crucial to the fermentation and more about the liquid keeping everything anaerobic, right?

Liquid, or moisture level, is huge to the movement and action of microbes in a ferment. Controlling the moisture level is a big part of guiding the microbes to achieve what you are aiming for in a ferment.

If we step back a moment and look at the natural world, well the larger visible natural world, we see that the more moisture there is the more things grow—a rainforested jungle vs a desert, for example. In one place diversity of all life flourished and you cannot keep growth back no matter how hard you try. In the other, your only hope for life is water. No water no life. Where there is water there is decay, quick decay of anything organic, and slower mineral. In the other, a humble corn cob undisturbed will stay unchanged for 1000 years. These are two extremes but brought into the kitchen can be seen as the preservation techniques of brine fermentation and dehydration--a jar of cucumber pickles and dried beans.

What if we put the two techniques together?

In most home fermentation currently practiced in this country, moisture, often in the form of brine, is added to the ferment as insurance to a successful ferment. I want to talk about removing moisture as a way to ensure success. This is nothing new but I think should be explored further.

In northern climates, storage is cool sheds or underground, which was enough to keep a briny ferment, or even some of the vegetables themselves, in relatively good shape until the first harvests of fresh greens were in. However, historically, in warmer tropical climates, where there was not only no refrigeration, a very recent invention of tools of food preservation, and temperatures that promoted microbial growth, combined to very quick decay. To stabilize their fresh foods during seasons of harvest and abundance people came up with ways to extend their foodstuffs by reducing the moisture. Food dehydration on its own is a powerful preservation technique, yet in some places, dehydration can be difficult to achieve and maintain. I am looking at you tropical climates with your high humidity and extreme rainy seasons. As a child, I lived on the tiny island of Ambon, in the Maluka Islands. It was the early 70s. What I didn’t know then was that I was experiencing foodways that were still intact. Electricity and all its conveniences had not reached our little village of Ari and there were a few months out of the year when nothing dried out. The rain didn’t stop and when it did the humidity was just as wet. Tempeh (originally from Java, not this region) grew well, sago starch fermented, and during that season dried goods suffered as algae grew on walls. It was, still is, a microbial paradise. Of course, these places have less need for food preservation in the way a northern climate does, as fresh food grows year-round, and fish is (or was) plentiful.

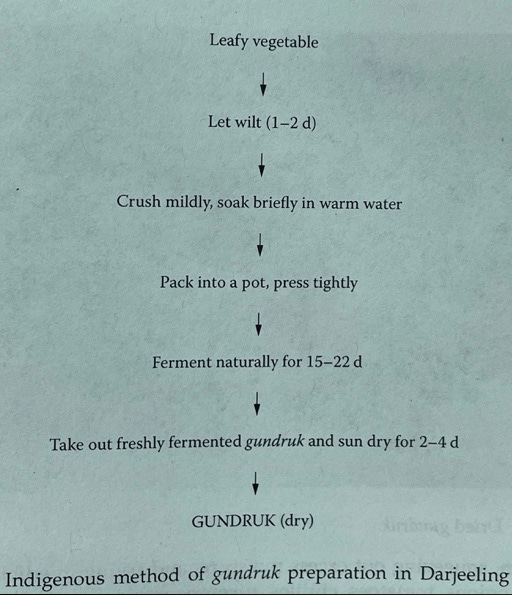

Across the world, people developed preservation techniques that were based on their needs, their foods, and their climates. In many parts of the world, people combined dehydration with fermentation to give foods super flavor and super-preservation power. One example is the leafy green ferment from Himalayan cultures, Gundruk.

These are unique in that the vegetable is dehydrated to some extent, then fermented, and after fermentation, fully dehydrated. The advantage is the fermentation has added a bunch of flavors as well as acidity to keep unwanted microorganisms out.

Moisture reduction improves stability, shelf life, and texture. It’s funny isn’t it, one thinks of wilted vegetables as limp. And limp vegetables as soggy or mushy—unpleasant. And yet that is exactly what we are doing, wilting our vegetables on purpose to do the opposite—increases the crispness and the crunch of the vegetables.

There are two main ways to reduce moisture. One is dehydration with sun or air or both.

When using dehydration before fermentation you are not dehydrating to the point of shelf stability by fully drying things out, you are simply reducing moisture. In doing so, we are limiting the microbial action, or simply put, slowing down the fermentation. Dehydration is also used after fermentation but in that case, it is to arrest the microbe activity completely (like us they need water to function) to stabilize food for storage. Dried inactive foodstuffs also take up much less pressure space or weight in a society that migrates seasonally. The other is using salt and pressure to draw out excess moisture.

Why one over the other? I like to think of it as another dial you can turn to achieve your fermentation goals. Right cuz we all know we are not in charge. So, it depends on your goals. The main advantage of dehydration is less salt use. In some cases, energy saving as in passively taking advantage of natural conditions. Often the proper moisture reduction by drying can give you a textural advantage with a crunchier end product.

The advantage of salting is that you are likely beginning the fermentation at the same time as the moisture reduction. You are less likely to over-dehydrate something. The salt pressing can offer other advantages like in the case of eggplants where any bitter flavors will be drawn out.

And so, here we are, finally talking about this week’s ⭐️

Eggplants have gone from a ferment that I was reluctant to try, nearly two decades ago, to one of my favorite ferments. For those of you that enjoy reading scientific studies, I found one this week (it’s short) that looks at fermented eggplant’s antioxidant content. Turns out unfermented eggplant is one of the top ten veggies in terms of antioxidants and polyphenols* found in the flesh and skin. The finding was that lactic acid fermentation did increase antioxidant activity. Interestingly, these levels were highest on day 3, and while they decreased as fermentation progressed. The fermented eggplants continued to remain higher in these compounds than the fresh raw eggplant.

In this week’s paid post I will be sharing how I use moisture reduction to create oil-preserved vegetables and a recipe for Fermented Eggplant in Olive Oil.

I hope were ever you are the weather and the week are treating you kindly.

I would love to hear about your experiences in the comments.

What are some of your other favorite ways to ferment eggplant that don’t involve oil?

Oooh this has given me lots to think about and thanks for sharing your experiences about growing up in Ambon. We are a long way from the coast and when pandemic lockdowns started I stocked up on salt so I could continue fermenting as much as possible! Apparently inland coconut trees also do well with a good fertilizing of salt. I’ve watched our cow try to knock over and then lick the mud from termite mounds and have wondered whether, apart from possible essential minerals, the mounds may also have some small concentration of salts....

I’ve never tried the partial drying but will keep it in mind, thanks always for the lovely ideas and inspiration! ❤️