Fermentation of Place: Cortes Island, BC edition

A postcard from the residency at Hollyhock Retreat Center, Cortes Island, BC

I believe place shapes us.

Can we better know ourselves by interacting with a place? I think that by actively engaging with the place we are in at any moment, or the place that we came from, we can learn more about our sense of who we are. Where we grew up likely formed the scaffolding, where we live now continues to form us, and the places we have lived or even have visited leave their mark on what it means to be.

This can be comforting, especially when a place is home and feels like home. Twenty-six years ago I fully embraced this bit of hillside ground surrounded by forest. My intensity was fueled by a childhood that felt unmoored. My childhood family called many places home. When I was a mother I wanted something different. (Around the Farmstead Table and a conversation with myself and our son Jakob who is raising his family here.) Yet I also miss all of those places. Each left its mark, defines who I am now, and each still has a small tug on my heart.

Visiting and Fermenting on Cortes Island

Last week I led a workshop on Cortes Island in Canada, the traditional and ancestral territories of the toq qaymɩxʷ (Klahoose), ɬəʔamɛn qaymɩxʷ (Tla'amin), ʔop qaymɩxʷ (Homalco) Nations. An island that is part of an archipelago that lies on the northern end of the Salish Sea called the Discovery Islands. These islands lie north beyond the Canadian Gulf Islands, which again sit north of Washington state’s San Juan Islands.

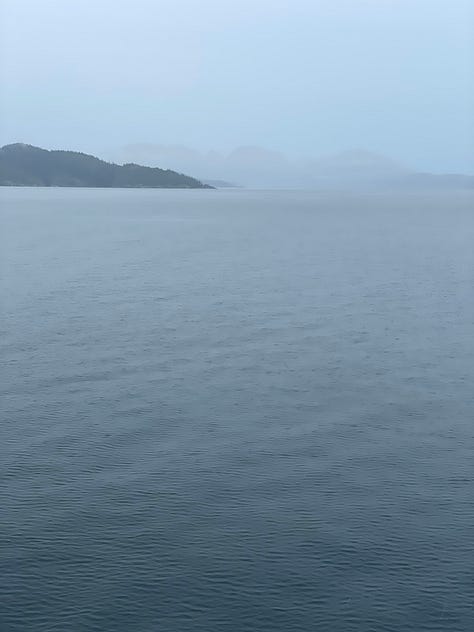

If you look on a map, it is where the sea becomes narrow as it appears to be squeezed between the British Columbia mainland and Vancouver Island. The sea becomes thready, broken up by the islands and long inlets. This makes the geography magnificently complex and disorienting. It was often difficult to decide which coastline with its distant mountains I was looking at from either of the two ferries it took to arrive (and depart) Cortes Island. I can only imagine how lost one could get, which apparently people counted on during the Vietnam War. I was told these islands were a place people went to be lost to society and the draft.

The workshop was titled Fermentation of Place. Because in many ways fermentation shows us the symbiotic relationship we have with the places with live and this planet. Let’s back up a moment.

Today though, I am talking about place as the main character, not the humans and the culture, though that is inextricably part of it. As impossible as it is to separate a piece from the whole for this moment, I want you to think about the physical space you move through life in.

The tree outside your door, the steps up to your apartment, the hillocks or mountains or concrete buildings in the near or far view, the sidewalks, the trill of crickets, or the hum and roar of traffic. Okay, now let’s let that recede into the background as well. What if we then move beyond the tangible, move beyond the physical environment we can see?

This is what I was hoping to do: help people use what is around them, both perceptible and microbial, to tap into what is us. (Even this isn’t woo-woo or nebulous thinking if you consider that estimates range wildly but generally agree that microbial cells in and on us outnumber our human cells.) In exploring the fermentation of food, we are also inviting ourselves to explore that we are not other—we are part of. We are part of nature always, even when surrounded by human-built environments.

The air was moist and crisp, fall seemed to be entering with a gentle touch. Despite the rain, the sea was mostly glassy. The garden was being tucked in for the winter yet still resplendent with colorful dahlias. The gnarled apple trees in the conifer-surrounded forest were slowly turning inward. Yellowing leaves and red fruit clung to their branches. Ferns glistened and fungi poked up from earthy duff.

We made cider and vinegar. Within a day of pressing the wild yeast on the apples showed us they were not only viable but strong—the effervescent show they put on was perfect to bring home the point of all the life that is around us. It is magical, and even a little less lonely, to see these microbes interacting with us. They do, of course, regardless of our attention or choices. But when specifically choose to collaborate with them when making food we get a sense of who they are through flavor and that flavor is different from place to place. We made wild yeast starters from flowers.

We scooped seawater and dehydrated it to make salt. We compared the flavor of this salt to salts I brought from other parts of the world. We made seaweed kimchi. (It is too late in the season for sea vegetable harvest, so we learned about the local kinds, tasted them and added small amounts. The bulk was Pacific Dulse I brought from a farm in Oregon.) We pickled vegetables that included chard stems from Hollyhock’s garden (the kitchen only needed the leaves).

We made miso, enlivened by everyone’s hands, and island chanterelles, kindly donated by another session’s student. This ferment will continue to build and transform for many months and I believe will be a delicious reminder of when 14 people fermented together on a far-flung island.

Getting home: It turns out certain US vegetables “lose their citizenship when they cross the border.”

Fermented vegetables, aged misos, vegetables in miso, homemade vinegars, currently bubbling and fermenting seaweed, early-stage (even more active) apple juice fermenting to cider, koji rice (but not basmati rice), and natto are okay. If only I had salted and jarred the lemon, mashed the peppers for hot sauce, and brined the okra and cherry tomatoes.

I know this because the dog smelled everything we had with us and the human pulled it all out of boxes and bins.

When we went through the checkpoint we were asked if we had any agricultural products. I hadn’t really thought about what we had with us because we hadn’t purchased anything in Canada. We stocked our camping food supplies at home. I tried to remember what we might have since the days prior to this we had been eating at the retreat center. (Had I mentioned how nice it is to teach a 4-day workshop with 3 meals a day being prepared for you and your students!) I sputtered out, oh there is a cauliflower, um, cherry tomatoes, um…at which point I was chastised for wasting their time. Didn’t I know I needed to have a list written out to hand them with my passport?

No, I didn’t. I have never come back into the US via a car. We were told to pull aside, leave our keys and go into the building. An hour and a half later the agriculture agent came to speak to us. We will call him Mr. T.

Mr. T was kind (unlike the first agent) and patiently explained to us the US Agriculture protection rules. His spiel was peppered with humor I am sure in an attempt to ease the tension of clueless people like us, who could be charged a large fine. He allowed me to explain that we’d bought the veggies at home and we didn’t argue as he explained that they lost their citizenship. He told us that the list (previously mentioned) is important to protect us. When we list the food the responsibility is on them. Anything we don’t claim, and I presume they discover, the responsibility and “mean words” is on us. The mean words being the large sums of money that they would demand from us. He still hadn’t told us if we would be fined.

“And never, ever bring firewood,” he said. “Firewood is a problem for me to get rid of, which makes it a problem for you.”

After our education, we went out to our vehicle with Mr. T, where our questionable goods were displayed. The vegetables landed in his trash sack. The 6 pounds of koji rice took some discussion. I explained aspergillus oryzae, enzymes, sake making…he wasn’t sure what I was talking about but decided since it wasn’t basmati, it was okay. Whew.

He shook our hand and said, “Welcome home. And remember don’t travel with firewood.” In my nervous relief, I sputtered out, “Won’t happen. I don’t even like campfires. We have had so many smoky summers in the last decade, the smell of a campfire is not soothing, it is a trigger of living near forest fires.”

I didn’t say, in the future, I will eat or ferment any vegetables on my way to the border.

Of all the stories you and Christopher have experienced at Customs, all over the world, this has to be the most intriguing. But I shall certainly sleep better tonight knowing the US Customs officers understand that Canadian microbes in fermented food are not nefarious!

This is like Aussie customs, so strict! I’m surprised you haven’t had this sort of treatment before. What a waste though, sigh